Heart attack and acute coronary syndrome

Highlights

Heart Attack Symptoms

Common signs and symptom of heart attack include:

- Chest pain or discomfort (angina), which can feel like pressure, squeezing, fullness, or pain in the center of the chest. With heart attack, the pain usually lasts for more than a few minutes, but it may increase and decrease in intensity.

- Discomfort in the upper body including the arms, neck, back, jaw, or stomach

- Shortness of breath, which can occur with or without chest pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Breaking out in cold sweat

- Lightheadedness or fainting

- Women (and some men) may have atypical symptoms such as abdominal distress, nausea, and fatigue without chest pain.

Immediate Treatment of a Heart Attack

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology recommend:

- If you think you are having a heart attack, call 911 right away. After you call 911, chew an adult-size (325 mg) non-coated aspirin. Be sure to tell the paramedics so an additional aspirin dose is not given.

- Angioplasty, also called percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is a procedure that should be performed within 90 minutes of a full-thickness (STEMI) heart attack. Patients suffering a heart attack should be transported by emergency services to hospitals equipped to perform PCI.

- Fibronolytic (“clot-busting”) therapy should be given within 30 minutes of a heart attack if a center that performs PCI is not available. The patient should then be transferred to a PCI facility without delay.

Secondary Prevention of Heart Attack

Secondary prevention measures are essential to help prevent another heart attack. Do not leave the hospital without discussing these secondary prevention steps with your doctor:

- High blood pressure and cholesterol control. (Nearly all patients who have had a heart attack should be discharged from the hospital with a prescription for a statin drug, an ACE inhibitor, and a beta blocker).

- Low-dose (81 mg) aspirin, which most patients will need to take on an ongoing basis. Patients who cannot take aspirin may benefit from the anti-platelet drug clopidogrel (Plavix, generic). Prasugrel (Effient) and ticagrelor (Brilinta) are new antiplatelet drugs that may be used as an alternative to clopidogrel for select patients with acute coronary syndrome. Patients who have had angioplasty/PCI along with drug-eluting stent placement will need to take one of these antiplatelets along with aspirin for at least a year following surgery.

- Cardiac rehabilitation and regular exercise program

- Weight management

- Smoking cessation and avoidance of second-hand tobacco smoke

- An annual "flu" shot

New Drug Approvals

- In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ticagrelor (Brilinta) to reduce the risk of stroke in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association now recommend ticagrelor as alternatives to clopidogrel for patients with ACS. Ticagrelor is an antiplatelet drug that works differently from aspirin, clopidogrel, and prasugrel.

- In 2012, the FDA approved generic versions of clopidogrel (Plavix).

Introduction

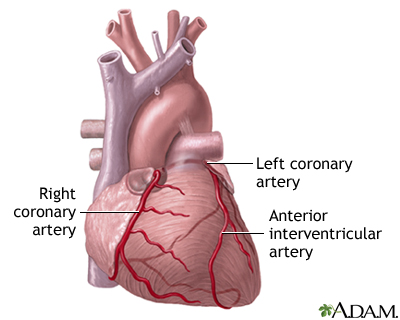

The heart is the human body's hardest working organ. Throughout life it continuously pumps blood enriched with oxygen and vital nutrients through a network of arteries to all tissues of the body. To perform this strenuous task, the heart muscle itself needs a plentiful supply of oxygen-rich blood, provided through a network of coronary arteries. These arteries carry oxygen-rich blood to the heart's muscular walls (the myocardium).

A heart attack (myocardial infarction) occurs when blood flow to the heart muscle is blocked, and tissue death occurs from loss of oxygen, severely damaging a portion of the heart.

Coronary Artery Disease. Coronary artery disease causes nearly all heart attacks. Coronary artery disease is the end result of a complex process called atherosclerosis (commonly called "hardening of the arteries"). This causes blockage of arteries (ischemia) and prevents oxygen-rich blood from reaching the heart.

Heart Attack

Heart attack (myocardial infarction) is among the most serious outcome of atherosclerosis. It can occur as a result of one of two effects of atherosclerosis:

- If the plaque develops fissures or tears. Blood platelets adhere to the site to seal off the plaque, and a blood clot (thrombus) forms. A heart attack can then occur if the blood clot completely blocks the passage of oxygen-rich blood to the heart.

- If the artery becomes completely blocked after gradual buildup of plaque due to atherosclerosis. Heart attack may occur if not enough oxygen-rich blood can flow past the blockage.

Angina

Angina, the primary symptom of coronary artery disease, is typically experienced as chest pain. There are two kinds of angina:

- Stable Angina. This is predictable chest pain that can usually be managed with lifestyle changes and medications, such as low-dose aspirin and nitrates.

- Unstable Angina. This situation is much more serious than stable angina, and is often an intermediate stage between stable angina and a heart attack. Unstable angina is part of a condition called acute coronary syndrome.

Acute Coronary Syndrome

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a severe and sudden heart condition that, although needing aggressive treatment, has not developed into a full blown heart attack. Acute coronary syndrome includes:

- Unstable Angina. Unstable angina is potentially serious and chest pain is persistent, but blood tests do not show markers for heart attack.

- NSTEMI (Non ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction). This condition, also called non Q-wave myocardial infarction, is diagnosed when blood tests and ECGs indicate a heart attack that does not involve the full thickness of the heart muscle. The injury in the arteries is less severe than with a full-blown heart attack.

Patients diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) may be at risk for a major heart attack. Doctors use a patient's medical history, various tests, and the presence of certain factors to help predict which ACS patients are most at risk for developing a more serious condition. The severity of chest pain itself does not necessarily indicate the actual damage in the heart.

Risk Factors

The risk factors for heart attack are the same as those for coronary artery disease (heart disease). They include:

Age

The risks for coronary artery disease increase with age. About 85% of people who die from heart disease are over the age of 65. For men, the average age of a first heart attack is 66 years.

Gender

Men have a greater risk for coronary artery disease and are more likely to have heart attacks earlier in life than women. Women’s risk for heart disease increases after menopause, and they are more likely to have angina than men.

Genetic Factors and Family History

Certain genetic factors increase the likelihood of developing important risk factors, such as diabetes, elevated cholesterol and high blood pressure.

Race and Ethnicity

African-Americans have the highest risk of heart disease in part due to their high rates of severe high blood pressure as well as diabetes and obesity.

Medical Conditions

Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Excess body fat, especially around the waist, can increase the risk for heart disease. Obesity also increases the risk for other conditions (such as high blood pressure and diabetes) that are associated with heart disease. Obesity is particularly hazardous when it is part of the metabolic syndrome, a pre-diabetic condition that is significantly associated with heart disease. This syndrome is diagnosed when three of the following are present:

- Abdominal obesity

- Low HDL cholesterol

- High triglyceride levels

- High blood pressure

- Insulin resistance (diabetes or pre-diabetes)

There are many ways to control your weight.

Unhealthy Cholesterol Levels. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol is the "bad" cholesterol responsible for many heart problems. Triglycerides are another type of lipid (fat molecule) that can be bad for the heart. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol is the "good" cholesterol that helps protect against heart disease. Doctors test for a "total cholesterol" profile that includes measurements for LDL, HDL, and triglycerides. The ratio of these lipids can affect heart disease risk.

High Blood Pressure.High blood pressure (hypertension) is associated with coronary artery disease and heart attack. For an adult, a normal blood pressure reading is below 120/80 mm Hg. High blood pressure is generally considered to be a blood pressure reading greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg (systolic) or greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg (diastolic). Blood pressure readings in the prehypertension category (120 - 139 systolic or 80 - 89 diastolic) indicate an increased risk for developing hypertension.

Diabetes. Diabetes, especially for people whose blood sugar levels are not well controlled, significantly increases the risk of developing heart disease. In fact, heart disease and stroke are the leading causes of death in people with diabetes. People with diabetes, both type 1 and type 2, are also at risk for high blood pressure and unhealthy cholesterol levels, blood clotting problems, kidney disease, and impaired nerve function, all of which can damage the heart.

Lifestyle Factors

Physical Inactivity. Exercise has a number of effects that benefit the heart and circulation, including improving cholesterol levels and blood pressure and maintaining weight control. People who are sedentary are almost twice as likely to suffer heart attacks as are people who exercise regularly.

Smoking.Smoking is the most important risk factor for heart disease. Smoking can cause elevated blood pressure, worsen lipids, and make platelets very sticky, raising the risk of clots. Although heavy cigarette smokers are at greatest risk, people who smoke as few as three cigarettes a day are at higher risk for blood vessel abnormalities that endanger the heart. Regular exposure to passive smoke also increases the risk of heart disease in nonsmokers.

Alcohol. Moderate alcohol consumption (one or two glasses a day) can help boost HDL “good” cholesterol levels. Alcohol may also prevent blood clots and inflammation. By contrast, heavy drinking harms the heart. In fact, heart disease is the leading cause of death in alcoholics.

Diet.Diet plays an important role in protecting the heart, especially by reducing dietary sources of trans fats, saturated fats, and cholesterol and restricting salt intake that contributes to high blood pressure.

NSAIDs and COX-2 Inhibitors

All nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) -- with the exception of aspirin -- carry heart risks. NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors may increase the risk for death in patients who have experienced a heart attack. The risk is greatest at higher dosages but some research suggests that even low doses of NSAIDs taken for short periods of time are not safe after a heart attack.

NSAIDs include nonprescription drugs like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, generic) and prescription drugs like diclofenac (Cataflam, Voltaren, generic). Celecoxib (Celebrex) is currently the only COX-2 inhibitor that is available in the U.S. It has been linked to cardiovascular risks, such as heart attack and stroke. Patients who have had heart attacks should talk to their doctors before taking any of these drugs.

The American Heart Association recommends that patients who have, or who are at risk for, heart disease first try non-drug methods of pain relief (such as physical therapy, exercise, weight loss to reduce stress on joints, and heat or cold therapy). If these methods don't work, patients should take the lowest effective and safe dose of acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) or aspirin before using an NSAID. The COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib (Celebrex) should be a last resort.

Prognosis

Heart attacks may be rapidly fatal, evolve into a chronic disabling condition, or lead to full recovery. The long-term prognosis for both length and quality of life after a heart attack depends on its severity, the amount of damage sustained by the heart muscle, and the preventive measures taken afterward.

Patients who have had a heart attack have a higher risk of a second heart attack. Although no tests can absolutely predict whether another heart attack will occur, patients can avoid having another heart attack by healthy lifestyle changes and adherence to medical treatments. Two-thirds of patients who have suffered a heart attack, however, do not take the necessary steps to prevent another.

Heart attack also increases the risk for other heart problems, including heart failure, abnormal heart rhythms, heart valve damage, and stroke.

Higher Risk Individuals. A heart attack is always more serious in certain people, including:

- Elderly

- People with a history of heart disease or multiple risk factors for heart disease

- People with heart failure

- People with diabetes

- People on long-term dialysis

Women are more likely to die from a heart attack than men. The gender difference is largest in younger patients.

Factors Occurring at the Time of a Heart Attack that Increase Severity. The presence of other conditions during a heart attack can contribute to a poorer outlook:

- Arrhythmias (disturbed heart rhythms). A dangerous arrhythmia called ventricular fibrillation is a major cause of early death from heart attack. Arrhythmias are more likely to occur within the first 4 hours of a heart attack, and they are associated with a high mortality rate. Patients who are successfully treated, however, have the same long-term prognosis as those who do not have such arrhythmias.

- Cardiogenic shock. This very dangerous condition is associated with very low blood pressure, reduced urine levels, and cellular abnormalities. Shock occurs in about 7% of heart attacks.

- Heart block, also called atrioventricular (AV) block, is a condition in which the electric conduction of nerve impulses to muscles in the heart is slowed or interrupted. Although heart block is dangerous, it can be treated effectively with a pacemaker, and it rarely causes any long-term complications in patients who survive it.

- Heart failure. The damaged heart muscle is unable to pump all the blood that the tissues need. Patients experience fatigue, shortness of breath, and fluid build-up.

Symptoms

Heart Attack Symptoms

Heart attack symptoms can vary. They may come on suddenly and severely or may progress slowly, beginning with mild pain. Symptoms can also vary between men and women. Women are less likely than men to have classic chest pain, but they are more likely to experience shortness of breath, nausea or vomiting, or jaw and back pain.

Common signs and symptom of heart attack include:

- Chest pain. Chest pain or discomfort (angina) is the main sign of a heart attack. It can feel like pressure, squeezing, fullness, or pain in the center of the chest. Patients with coronary artery disease who have stable angina often experience chest pain that lasts for a few minutes and then goes away. With heart attack, the pain usually lasts for more than a few minutes and the feeling may go away but then come back.

- Discomfort in the upper body. People having a heart attack may feel discomfort in the arms, neck, back, jaw, or stomach.

- Shortness of breath can occur with or without chest pain.

- Nausea and vomiting

- Breaking out in cold sweat

- Lightheadedness or fainting

Symptoms That Are Less Likely to Indicate Heart Attack

The following symptoms are less likely to be due to heart attack:

- Sharp pain brought on by breathing in or when coughing

- Pain that is mainly or only in the middle or lower abdomen

- Pain that can be pinpointed with the tip of one finger

- Pain that can be reproduced by moving or pressing on the chest wall or arms

- Pain that is constant and lasts for hours (although no one should wait hours if they suspect they are having a heart attack)

- Pain that is very brief and lasts for a few seconds

- Pain that spreads to the legs

However, the presence of these symptoms does not always rule out a serious heart event.

Silent Ischemia

Some people with severe coronary artery disease do not have angina pain. This condition is known as silent ischemia. This is a dangerous condition because patients have no warning signs of heart disease. Some studies suggest that people with silent ischemia experience higher complication and mortality rates than those with angina pain.

What to Do When Symptoms Occur

People who have symptoms of a heart attack should take the following actions:

- For angina patients, take one nitroglycerin dose either as an under-the-tongue tablet or in spray form at the onset of symptoms. Take another dose every 5 minutes up to three doses or when the pain is relieved, whichever comes first.

- Call 911 or the local emergency number. This should be the first action taken if angina patients continue to experience chest pain after taking the full three doses of nitroglycerin. However, only 20% of heart attacks occur in patients with previously diagnosed angina. Therefore, anyone who develops heart attack symptoms should contact emergency services.

- The patient should chew and swallow an uncoated adult-strength (325 mg) aspirin and be sure to tell emergency health providers so an additional dose is not given.

- Patients with chest pain should go immediately to the nearest emergency room, preferably traveling by ambulance. They should not drive themselves.

Diagnosis

When a patient comes to the hospital with chest pain, the following diagnostic steps are usually taken to determine any heart problems and, if present, their severity:

- The patient will report all symptoms so that a health care provider can rule out either a non-heart problem or possible other serious accompanying conditions.

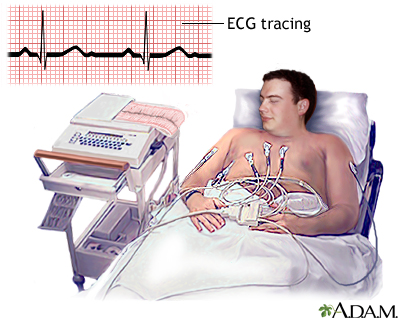

- An electrocardiogram (ECG) reading is taken, recording the electrical activity of the heart. It is the key tool for determining if heart problems are causing chest pain and, if so, how severe they are.

- Blood tests showing elevated levels of certain factors (troponins and CK-MB) indicate heart damage. (The doctor will not wait for results, however, before administering treatment if a heart attack is strongly suspected.)

- Imaging tests, including echocardiogram and perfusion scintigraphy, help rule out a heart attack if there is any question.

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

An electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) measures and records the electrical activity of the heart. The waves measured by the ECG correspond to the contraction and relaxation pattern of the different parts of the heart. Specific waves seen on an ECG are named with letters:

- P. The P wave is associated with the contractions of the atria (the two chambers in the heart that receive blood from outside).

- QRS. The QRS is a series of waves associated with ventricular contractions. (The ventricles are the two major pumping chambers in the heart.)

- T and U. These waves follow the ventricular contractions.

Doctors use a term called the P-Q or P-R interval, which is the time taken for an electrical impulse to travel from the atria to the ventricle.

The most important wave patterns in diagnosing and determining treatment for a heart attack are called ST elevations and Q waves.

Elevated ST Segments: Heart Attack. Elevated ST segments are strong indicators of a heart attack in patients with symptoms and other indicators. They suggest that an artery to the heart is blocked and that the full thickness of the heart muscle is damaged. The kind of heart attack associated with these findings is referred to as either a Q-wave myocardial infarction or a STEMI (ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction).

However, ST segment elevations do not always mean the patient has a heart attack. For example, an inflammation in the sack around the heart (pericarditis) is another cause of ST-segment elevation.

Non-Elevated ST Segments: Angina and Acute Coronary Syndrome. A depressed or horizontal ST wave suggests some blockage and the presence of heart disease, even if there is no angina present. It occurs in about half of patients with other signs of a heart event. This finding, however, is not very accurate, particularly in women, and can occur without heart problems. In such cases, laboratory tests are needed to determine the extent, if any, of heart damage. In general, one of the following conditions may be present:

- Stable Angina (blood test results or other tests show no serious problems and chest pain resolves). Between 25 - 50% of people who have angina or silent ischemia have normal ECG readings.

- Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS). This includes severe and sudden heart conditions that require aggressive treatment but have not developed into a full-blown heart attack. ACS refers to either unstable angina or NSTEMI (non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction), also referred to as non Q-wave myocardial infarction. Unstable angina is potentially serious, and chest pain is persistent, but blood tests do not show markers for heart attack. With NSTEMI, the blood tests indicate a heart attack, but in most cases, injury to the heart is less serious than with a full-blown STEMI heart attack.

Echocardiogram

An echocardiogram is a noninvasive test that uses ultrasound images of the heart. Your doctor can see whether a part of your heart muscle has been damaged and is not moving. An echocardiogram may also be used as part of an exercise stress test, to detect the location and extent of heart muscle damage at the time of discharge or soon after you leave the hospital after a heart attack.

Radionuclide Imaging (Thallium Stress Test)

Radionuclide procedures use imaging techniques and computer analyses to plot and detect the passage of radioactive tracers through the region of the heart. Such tracing elements are typically given intravenously. Radionuclide imaging is useful for diagnosing and determining:

- Severity of unstable angina when less expensive diagnostic approaches are unavailable or unreliable

- Severity of chronic coronary artery disease

- Success of surgeries for coronary artery disease

- Whether a heart attack has occurred

- The location and extent of heart muscle damage at the time of discharge or soon after you leave the hospital after a heart attack

The procedure is noninvasive. It is a reliable measure of severe heart events and can help identify if damage has occurred from a heart attack. A radioactive isotope such as thallium (or technetium) is injected into the patient's vein. The radioactive isotope attaches to red blood cells and passes through the heart in the circulating blood. The isotope can then be traced through the heart using special cameras or scanners. The images may be combined with an electrocardiogram. The patient is tested while resting, then tested again during an exercise stress test. If the scan detects damage, more images are taken 3 or 4 hours later. Damage due to a prior heart attack will persist when the heart scan is repeated. Injury caused by angina, however, will have resolved by that time.

Angiography

Angiography is an invasive test. It is used for patients who show strong evidence for severe obstruction on stress and other tests and for patients with acute coronary syndrome. In the procedure:

- A narrow tube is inserted into an artery, usually in the leg or arm, and then threaded up through the body to the coronary arteries.

- A dye is injected into the tube, and an x-ray records the flow of dye through the arteries.

- This process provides a map of the coronary circulation, revealing any blocked areas.

Biologic Markers

When heart cells become damaged, they release different enzymes and other molecules into the bloodstream. Elevated levels of such markers of heart damage in the blood or urine may help predict a heart attack in patients with severe chest pain, and help determine treatment. Tests for these markers are often performed in the emergency room or hospital when a heart attack is suspected. Some markers include:

- Troponins. The proteins cardiac troponin T and I are released when the heart muscle is damaged. Both are proving to be among the best diagnostic indications of heart attacks. They can help diagnose heart attack and identify patients with ACS who might otherwise be misdiagnosed.

- Creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB). CK-MB has been a standard marker, but the MB fraction is not as accurate as troponin levels, since elevated levels can appear in people without heart injury.

Treatment

Treatment options for heart attack, and acute coronary syndrome, include:

- Oxygen therapy

- Relieving pain and discomfort using nitroglycerin or morphine

- Controlling any arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms)

- Blocking further clotting (if possible), using an anti-platelet drug such as aspirin or clopidogrel (Plavix, generic), or other clot-fighting drugs such as heparin and special medications called glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, or the newer drug bivalirudin

- Opening up the artery that is blocked as soon as possible, by performing angioplasty or using medicines that open up the clot

- Giving the patient beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, or ACE inhibitor drugs to help the heart muscle and arteries work better

Immediate Treatments to Support the Patient

Early supportive treatments are similar for patients who have ACS or those who have had a heart attack.

Oxygen. Oxygen is almost always administered right away, usually through a tube that enters through the nose.

Aspirin. The patient is given aspirin if one was not taken at home.

Medications for Relieving Symptoms.

- Nitroglycerin. Most patients will receive nitroglycerin during and after a heart attack, usually under the tongue. Nitroglycerin decreases blood pressure and opens the blood vessels around the heart, increasing blood flow. Nitroglycerin may be given intravenously in certain cases (recurrent angina, heart failure, or high blood pressure).

- Morphine. Morphine not only relieves pain and reduces anxiety but also opens blood vessels, aiding the circulation of blood and oxygen to the heart. Morphine can decrease blood pressure and slow down the heart. In patients in whom such effects may worsen their heart attacks, other drugs may be used.

Opening the Arteries: Emergency Angioplasty or Thrombolytic Drugs

With a heart attack, clots form in the coronary arteries that supply oxygen to the heart muscle. Opening a clotted artery as quickly as possible is the best approach to improving survival and limiting the amount of heart muscle that is permanently damaged. New guidelines recommend that communities have emergency systems in place to ensure that heart attack patients are directed to appropriate medical centers equipped to treat them as quickly as possible.

The standard medical and surgical solutions for opening arteries are:

- Angioplasty, also called percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is the preferred emergency procedure for opening the arteries. Angioplasty should be performed promptly for patients with STEMI heart attack, preferably within 90 minutes of arriving at a hospital capable of performing the procedure. In most cases, a stent is placed in the artery to keep it open after the angioplasty.

- Thrombolytics (clot-busting drugs) are the standard medications used to open the arteries. A thrombolytic drug needs to be given within 3 hours after the onset of symptoms. Patients who arrive at a hospital that is not equipped to perform PCI should receive clot-busting therapy and then be transferred to a PCI center without delay.

- Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is sometimes used as an alternative to angioplasty.

Thrombolytics

Thrombolytic, also called clot-busting or fibrinolytic, drugs are recommended as alternatives to angioplasty. These drugs dissolve the clot, or thrombus, responsible for causing artery blockage and heart-muscle tissue death.

Generally speaking, thrombolysis is considered a good option for patients with full-thickness (STEMI) heart attacks when symptoms have been present for fewer than 3 hours. Ideally, these drugs should be given within 30 minutes of arriving at the hospital if angioplasty is not a viable option. Other situations where a clot-busting drug may be used include when:

- Prolonged transport will be required

- Too long of a time will pass before a catheterization lab is available

- PCI procedure is not successful or anatomically too difficult

Thrombolytics should be avoided or used with great caution in the following patients after heart attack:

- Patients older than 75 years

- When symptoms have continued beyond 12 hours

- Pregnant women

- People who have experienced recent trauma (especially head injury) or invasive surgery

- People with active peptic ulcers

- Patients who have been given prolonged CPR

- Current users of anticoagulants

- Patients who have experienced any recent major bleeding

- Patients with a history of stroke

- Patients with uncontrolled high blood pressure, especially when systolic is higher than 180 mm Hg

Specific Thrombolytics. The standard thrombolytic drugs are recombinant tissue plasminogen activators or rt-PAs. They include alteplase (Activase) and reteplase (Retavase) as well as a newer drug tenecteplase (TNKase). Other types of drugs, such as a combination of an antiplatelet and anticoagulant, may also be given to prevent the clot from growing larger or any new clots from forming.

Thrombolytic Administration. The sooner that thrombolytic drugs are given after a heart attack, the better. The benefits of thrombolytics are highest within the first 3 hours. They can still help if given within 12 hours of a heart attack.

Complications. Hemorrhagic stroke, usually occurring during the first day, is the most serious complication of thrombolytic therapy, but fortunately it is rare.

Revascularization Procedures: Angioplasty and Bypass Surgery

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), also called angioplasty, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery are the standard operations for opening narrowed or blocked arteries. They are known as revascularization procedures.

- Emergency angioplasty/PCI is the standard procedure for heart attacks and should be performed preferably within 90 minutes of a heart attack. Studies have shown that balloon angioplasty and stenting fails to prevent heart complications in patients who receive the procedure 3 - 28 days after a heart attack.

- Coronary bypass surgery is typically used as elective surgery for patients with blocked arteries. It may be used after a heart attack if angioplasty or thrombolytics fail or are not appropriate. It is usually not performed for several days to allow recovery of the heart muscles.

Most patients who meet the criteria for either thrombolytic drugs or angioplasty do better with angioplasty (although only in centers equipped to do this procedure).

Angioplasty/PCI involves procedures such as percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) that help open the blocked artery. A typical angioplasty procedure involves the following steps:

- The cardiologist threads a narrow catheter (a tube) containing a fiber into the blocked vessel.

- The cardiologist opens the blocked vessel using balloon angioplasty, in which a tiny deflated balloon is passed through the catheter to the vessel.

- The balloon is inflated to compress the plaque against the walls of the artery, flattening it out so that blood can once again flow through the blood vessel freely.

- To keep the artery open afterwards, doctors use a device called a coronary stent, an expandable metal mesh tube that is implanted during angioplasty at the site of the blockage. The stent may be bare metal or it may be coated with a drug that slowly releases medication.

- Once in place, the stent pushes against the wall of the artery to keep it open.

Complications occur in about 10% of patients (about 80% of complications occur within the first day). Best results occur in hospital settings with experienced teams and backup. Women who have angioplasty after a heart attack have a higher risk of death than men.

Reclosure and Blockage During or After Angioplasty. Narrowing or reclosure of the artery (restenosis) often occurs during or shortly after angioplasty. It can also occur up to a year after surgery, requiring a repeat angioplasty procedure.

Drug-eluting stents, which are coated with everolimus, sirolimus, or paclitaxel, can help prevent restenosis. They may be better than bare metal stents for patients who have experienced a STEMI heart attack, but they can also increase the risks of blood clots.

It is very important for patients who have drug-eluting stents to take aspirin and clopidogrel (Plavix, generic) for at least 1 year after the stent is inserted, to reduce the risk of blood clots. Clopidogrel, like aspirin, helps to prevent blood platelets from clumping together.

Prasugrel (Effient) is a newer antiplatelet drug that may be used as an alternative to clopidogrel for select patients with acute coronary syndrome who are undergoing angioplasty. It should not be used by patients who have had a previous stroke or transient ischemic attack. Another option for patients with ACS is the new antiplatelet drug ticagrelor (Brilinta). Like clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor are taken in combination with aspirin.

If for some reason patients cannot take a second antiplatelet along with aspirin after angioplasty and stenting, they should receive a bare metal stent instead of a drug-eluting stent.

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery (CABG). Coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) is the alternative procedure to angioplasty for opening blocked arteries, particularly for patients who have two or more blocked arteries. It is a very invasive procedure, however:

- The chest is opened, and the blood is rerouted through a lung-heart machine.

- The heart is stopped during the procedure.

- Segments of veins or arteries taken from elsewhere in the patient's body are fashioned into grafts, which are used to reroute the blood. The blood vessel grafts are placed in front of and beyond the blocked arteries, so the blood flows through the new vessels around the blockage.

Treatment for Patients in Shock or with Heart Failure

Severely ill patients, particularly those with heart failure or who are in cardiogenic shock (a dangerous condition that includes a drop in blood pressure and other abnormalities), will be monitored closely and stabilized. Oxygen is administered, and fluids are given or replaced when it is appropriate to either increase or reduce blood pressure. Such patients may be given dopamine, dobutamine, or both. Other treatments depend on the specific condition.

Heart failure. Intravenous furosemide may be administered. Patients may also be given nitrates, and ACE inhibitors, unless they have a severe drop in blood pressure or other conditions that preclude them. Clot-busting drugs or angioplasty may be appropriate.

Cardiogenic Shock. A procedure called intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABP) can help patients with cardiogenic shock when used in combination with thrombolytic therapy. IABP involves inserting a catheter containing a balloon, which is inflated and deflated within the artery to boost blood pressure. Left ventricular assist devices and early angioplasty might also be considered.

Treatment of Arrhythmias

An arrhythmia is a deviation from the heart's normal beating pattern caused when the heart muscle is deprived of oxygen and is a dangerous side effect of a heart attack. A very fast or slow rhythmic heart rate often occurs in patients who have had a heart attack, and is not usually a dangerous sign.

Premature beats or very fast arrhythmias called tachycardia, however, may be predictors of ventricular fibrillation. This is a lethal rhythm abnormality, in which the ventricles of the heart beat so rapidly that they do not actually contract but quiver ineffectually. The pumping action necessary to keep blood circulating is lost.

Preventing Ventricular Fibrillation. People who develop ventricular fibrillation do not always experience warning arrhythmias, and to date, there are no effective drugs for preventing arrhythmias during a heart attack.

- Potassium and magnesium levels should be monitored and maintained.

- Intravenous beta blockers followed by oral administration of the drugs may help prevent arrhythmias in certain patients.

Treating Ventricular Fibrillation.

- Defibrillators. Patients who develop ventricular arrhythmias are given electrical shocks with defibrillators to restore normal rhythms. Some studies suggest that implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) may prevent further arrhythmias in heart attack survivors of these events who are at risk for further arrhythmias.

- Antiarrhythmic Drugs. Antiarrhythmic drugs include lidocaine, procainamide, or amiodarone. Amiodarone or another antiarrhythmic drug may be used afterward to prevent future events.

Managing Other Arrhythmias. People with an arrhythmia called atrial fibrillation have a higher risk for stroke after a heart attack and should be treated with anticoagulants such as warfarin (Coumadin, generic), dabigatran (Pradaxa), or rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Other rhythm disturbances called bradyarrhythmias (very slow rhythm disturbances) frequently develop in association with a heart attack and may be treated with atropine or pacemakers.

Medications

Aspirin and Other Anti-Clotting Drugs

Anti-clotting drugs that inhibit or break up blood clots are used at every stage of heart disease. They are generally classified as either anti-platelets or anticoagulants. Both anti-platelets and anticoagulants prevent blood clots from forming but they work in different ways. Anti-platelets prevent blood platelets from sticking together. Anticoagulants are “blood thinners” that stop blood from clotting. Anti-platelets and anticoagulants carry the risk of bleeding, which can lead to dangerous situations, including stroke.

Appropriate anticlotting medications are started immediately in all patients. Such drugs are sometimes used along with thrombolytics, and also as on-going maintenance to prevent a heart attack.

Anti-Platelet Drugs. These drugs inhibit blood platelets from sticking together, and therefore help to prevent clots. Platelets are very small disc-shaped blood cells that are important for blood clotting.

- Aspirin. Aspirin is an antiplatelet drug. An aspirin should be taken immediately after a heart attack begins. It can be either swallowed or chewed, but chewing provides more rapid benefit. If the patient has not taken an aspirin at home, it will be given at the hospital. It is then continued daily (usually 81 mg/day). Using aspirin for heart attack patients has been shown to reduce mortality. It is the most common anti-clotting drug, and most people with heart disease are advised to take it daily in low dose on an ongoing basis.

- Clopidogrel (Plavix, generic), a thienopyridine, is another type of anti-platelet drug. Clopidogrel is started either immediately or right after angioplasty/PCI is performed. It is also begun after thrombolytic therapy. Patients who receive a drug-eluting stent should take clopidogrel along with aspirin for at least 1 year to reduce the risk of clots. Some patients may need to take clopidogrel on an ongoing basis. Clopidogrel can increase the risk of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Discuss with your doctor whether you should take a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). PPIs can reduce the risk of GI bleeding but they also can interfere with clopidogrel’s anti-clotting effects. .

- Prasugrel (Effient) is a newer thienopyridine that may be used instead of clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). It should not be used by patients who have a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack.

- Ticagrelor (Brilinta) is another new antiplatelet approved for patients with ACS. It works differently than thienopyridines.

- Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors. These powerful anti-platelet drugs include abciximab (ReoPro), eptifibatide (Integrilin), and tirofiban (Aggrastat). They are administered intravenously in the hospital and are used with angioplasty/PCI or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

Anticoagulant Drugs. Anticoagulants thin blood. They include:

- Heparin is usually begun during or at the end of treatment with thrombolytic drugs and continued for at least 2 days if not the whole time in the hospital.

- Other intravenous anticoagulants that may be given in the hospital include bivalirudin (Angiomax), fondaparinux (Arixtra), and enoxaparin (Lovenox).

- Warfarin (Coumadin, generic). Dabigatran (Pradaxa) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) are other options for patients with atrial fibrillation.

All of these drugs pose a risk for bleeding.

Beta Blockers

Beta blockers reduce the oxygen demand of the heart by slowing the heart rate and lowering pressure in the arteries. They are effective for reducing deaths from heart disease. Beta blockers are often given to patients early in their hospitalization, sometimes intravenously. Patients with heart failure or who are at risk of going into cardiogenic shock should not receive intravenous beta blockers. Long-term oral beta blocker therapy for patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease, particularly after heart attacks, is recommended in most patients.

These drugs include propranolol (Inderal), carvedilol (Coreg), bisoprolol (Zebeta), acebutolol (Sectral), atenolol (Tenormin), labetalol (Normodyne, Trandate), metoprolol (Lopressor, Toprol-XL), and esmolol (Brevibloc). All of these drugs are available in generic form.

Administration During a Heart Attack. The beta blocker metoprolol may be given through an IV within the first few hours of a heart attack to reduce damage to the heart muscle.

Prevention After a Heart Attack. Beta blockers taken by mouth are also used on a long-term basis (as maintenance therapy) after a first heart attack to help prevent future heart attacks.

Side Effects. Beta blocker side effects include fatigue, lethargy, vivid dreams and nightmares, depression, memory loss, and dizziness. They can lower HDL (“good”) cholesterol. Beta blockers are categorized as non-selective or selective. Non-selective beta blockers, such as carvedilol and propranolol, can narrow bronchial airways. Patients with asthma, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis, should not take non-selective beta blockers.

Patients should not abruptly stop taking these drugs. The sudden withdrawal of beta blockers can rapidly increase heart rate and blood pressure. The doctor may want the patient to slowly decrease the dose before stopping completely.

Statins and Other Cholesterol and Lipid-Lowering Drugs

After being admitted to the hospital for acute coronary syndrome or a heart attack, patients should not be discharged without statins or other cholesterol medicine unless their LDL ("bad") cholesterol is below 100 mg/dL. Some doctors recommend that LDL should be below 70 mg/dL.

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are important drugs for treating patients who have had a heart attack, particularly for patients at risk for heart failure. ACE inhibitors should be given on the first day to all patients with a heart attack, unless there are medical reasons for not taking them. Patients admitted for unstable angina or acute coronary syndrome should receive ACE inhibitors if they have symptoms of heart failure or evidence of reduced left ventricular fraction echocardiogram. These drugs are also commonly used to treat high blood pressure (hypertension) and are recommended as first-line treatment for people with diabetes and kidney damage.

ACE inhibitors include captopril (Capoten), ramipril (Altace), enalapril (Vasotec), quinapril (Accupril), benazepril (Lotensin), perindopril (Aceon), and lisinopril (Prinivil, Zestril). All of these drugs are available in generic form.

Side Effects. Side effects of ACE inhibitors are uncommon but may include an irritating cough, excessive drops in blood pressure, and allergic reactions.

Calcium Channel Blockers

Calcium channel blockers may provide relief in patients with unstable angina whose symptoms do not respond to nitrates and beta blockers, or for patients who are unable to take beta blockers.

Secondary Prevention

Patients can reduce the risk for a second heart attack by following secondary prevention measures. No one should be discharged from the hospital with these issues being addressed and appropriate medications prescribed. Lifestyle choices, particularly dietary factors, are equally important in preventing heart attacks and must be strenuously adhered to.

Blood Pressure. Aim for a blood pressure of less than 130/80 mm Hg.

Cholesterol. LDL (“bad”) cholesterol should be substantially less than 100 mg/dL. If triglycerides are greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL, then non-HDL-C should be less than 130 mg/dL. [Non-HDL-C is the difference between total cholesterol and HDL (“good") cholesterol levels.] Nearly all patients who have had a heart attack should receive a prescription for a statin drug before being discharged from the hospital. It is also important to control dietary cholesterol by reducing intake of saturated fats to less than 7% of total calories. Increased omega-3 fatty acid consumption (by eating more fish or taking fish oil supplements) can help reduce triglyceride levels.

Exercise. Exercise for 30 - 60 minutes 7 days a week (or at least a minimum of 5 days a week).

Weight Management. Combine exercise with a healthy diet rich in fresh fruits, vegetables and low-fat dairy products. Your body mass index (BMI) should be 18.5 - 24.8. Waist circumference is also an important measure of heart attack risk. Men’s waist circumferences should be less than 40 inches (102 centimeters), while women’s should be below 35 inches (89 centimeters).

Smoking. It is essential to stop smoking. Also, avoid exposure to second-hand smoke.

Anti-Platelet Drugs. Your doctor may recommend you take low-dose aspirin (75 - 81 mg) on a daily basis. If you have had a drug-coated stent inserted, you must take another anti-platelet drug along with aspirin for at least 1 year following surgery. (Aspirin is also recommended for some patients as primary prevention of heart attack.)

Other Drugs. Your doctor may recommend that you take an ACE inhibitor or beta blocker drug on an ongoing basis. It is also important to have an annual influenza (“flu”) vaccination.

Rehabilitation

Physical Rehabilitation

Physical rehabilitation is extremely important after a heart attack. Patients with recent episodes of acute coronary syndrome also generally need some sort of supervised exercise training. Cardiac rehabilitation may include:

- Leg exercises may start as early as the first day. The patient usually sits in a chair on the second day, and begins to walk on the second or third day.

- Most patients undergo low-level exercise tolerance tests early in their recovery.

- After 8 - 12 weeks, many patients, even those with heart failure, benefit from supervised exercise programs. Health care providers should give the patient schedules for low-level aerobic home-activity. Strength (resistance) training is also important. In general, the risk for serious heart events during rehabilitation is very low.

Patients generally return to work in about 1 - 2 months, although timing can vary depending on the severity of the condition.

Sexual activity after a heart attack has a low risk and is generally considered safe, particularly for people who exercised regularly before the attack. The feelings of intimacy and love that accompany healthy sex can help offset depression.

Emotional Rehabilitation

Major depression occurs in many patients who have ACS or who have had heart attacks. Studies suggest that depression is a major predictor for increased mortality in both women and men. (One reason may be that depressed patients are less likely to comply with their heart medications.)

Guidelines now recommend depression screening for all patients who have had a heart attack. Psychotherapeutic techniques, especially cognitive behavioral therapies, may be very helpful. For some patients, certain types of antidepressant drugs may be appropriate.

Resources

- www.nhlbi.nih.gov -- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- www.acc.org -- American College of Cardiology

- www.heart.org -- American Heart Association

References

Abraham NS, Hlatky MA, Antman EM, Bhatt DL, Bjorkman DJ, Clark CB, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 Expert Consensus Document on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation. 2010 Dec 14;122(24):2619-33. Epub 2010 Nov 8.

Antman EM and Morrow DA. ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: management. In Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 9th ed. Saunders; 2012:chap 55.

Antman EM, Bennett JS, Daugherty A, Furberg C, Roberts H, Taubert KA. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007 Mar 27;115(12):1634-42. Epub 2007 Feb 26.

Baber U, Mehran R, Sharma SK, Brar S, Yu J, Suh JW, et al. Impact of the everolimus-eluting stent on stent thrombosis: a meta-analysis of 13 randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Oct 4;58(15):1569-77. Epub 2011 Sep 14.

Bradley EH, Nallamothu BK, Herrin J, Ting HH, Stern AF, Nembhard IM, et al. National efforts to improve door-to-balloon time results from the Door-to-Balloon Alliance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Dec 15;54(25):2423-9.

Cannon CP and Braunwald E. Unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 9th ed. Saunders; 2012:chap 56.

Eisenstein EL, Anstrom KJ, Kong DF, Shaw LK, Tuttle RH, Mark DB, et al. Clopidogrel use and long-term clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation. JAMA. 2007 Jan 10;297(2):159-68. Epub 2006 Dec 5.

Goodman SG, Menon V, Cannon CP, Steg G, Ohman EM, Harrington RA; et al. Acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008 Jun;133(6 Suppl):708S-775S.

Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, Bittl JA, Bridges CR, Byrne JG, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec 6;58(24):e123-210. Epub 2011 Nov 7.

Hirsch A, Windhausen F, Tijssen JG, Verheugt FW, Cornel JH, de Winter RJ; Invasive versus Conservative Treatment in Unstable coronary Syndromes (ICTUS) investigators. Long-term outcome after an early invasive versus selective invasive treatment strategy in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome and elevated cardiac troponin T (the ICTUS trial): a follow-up study. Lancet. 2007 Mar 10;369(9564):827-35.

Keller T, Zeller T, Ojeda F, Tzikas S, Lillpopp L, Sinning C, et al. Serial changes in highly sensitive troponin I assay and early diagnosis of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2011 Dec 28;306(24):2684-93.

Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC Jr, King SB 3rd, Anderson JL, Antman EM, et al. 2009 Focused Updates: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients WithST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (updating the 2004 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI Guidelines on Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (updating the 2005 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2009 Dec 1;120(22):2271-306. Epub 2009 Nov 18.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec 6;58(24):e44-122. Epub 2011 Nov 7.

Montalescot G, Cayla G, Collet JP, Elhadad S, Beygui F, Le Breton H, et al. Immediate vs delayed intervention for acute coronary syndromes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2009 Sep 2;302(9):947-54.

Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Chen J, Wang Y, Nallamothu BK, Epstein AJ, et al. Association of door-to-balloon time and mortality in patients admitted to hospital with ST elevation myocardial infarction: national cohort study. BMJ. 2009 May 19;338:b1807. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1807.

Schjerning Olsen AM, Fosbøl EL, Lindhardsen J, Folke F, Charlot M, Selmer C, et al. Duration of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and impact on risk of death and recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with prior myocardial infarction: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2011 May 24;123(20):2226-35. Epub 2011 May 9.

Smith SC Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, Braun LT, Creager MA, Franklin BA, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Nov 29;58(23):2432-46. Epub 2011 Nov 3.

Stone GW, Lansky AJ, Pocock SJ, Gersh BJ, Dangas G, Wong SC, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009 May 7;360(19):1946-59.

Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, Gutterman DD, Sonnenberg FA, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(2 Suppl):e637S-68S.

Wagner GS, Macfarlane P, Wellens H, Josephson M, Gorgels A, Mirvis DM, et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part VI: acute ischemia/infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):1003-11.

Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, Bridges CR, Casey DE Jr, Ettinger SM, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 May 10;57(19):e215-367.

|

Review Date:

5/24/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |